Back to page 3 Chinese Literati Painting -- Page 4 To page 5

The Early Height of Academic Painting in the Song

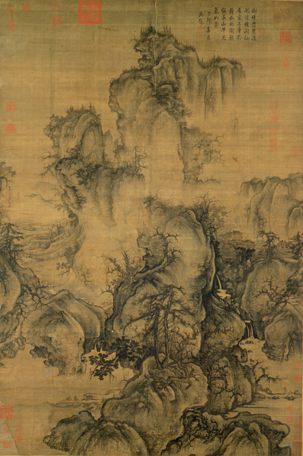

After many centuries where decorative painting and painting of human and animal figures were the most developed forms of visual art in China, landscape painting entered a period of sudden development during the Tang and early Song Dynasties. While we have almost no paintings from the Tang that remain, some of China's most famous paintings come from the early Song (the Northern Song period, 960-1127, before the invasion of North China forced the Song rulers into the South). These are monumental "hanging scrolls," very large paintings on silk that are mounted to hang on walls. They were composed by professional court artists, and the technique used in them departs from the "calligraphic" skills common to all literate people, and attempts to use a very complex array of brush strokes to convey an effect of "verisimilitude" (that is, the landscapes seem "real"). Here are two examples. The painting on the left is by Fan Kuan, and is called "Travelers By Streams and Mountains." (You can just see the travelers and their ox-carts, dwarfed by the landscape -- almost dots on this web version of the painting -- towards the bottom; click on the image for a much-enlarged view of them.) On the right is "Early Spring," by Guo Xi. To explore "Early Spring" more closely, click on the image for a large size version.

Despite the flourishing of the academic tradition during this period, the Northern Song is also the era that sees the initial sprouts of the monochrome ink style from which a new form of painting ultimately grew: literati style painting. The literati were the Confucian-trained men who had been groomed to pass the national civil service examinations, and while their education included mastery of the literature of history and thought, it also taught them the skills of poetry and calligraphy, and, for some, this led to an interest in painting as well. Not trained as technical experts in the academic style of painting, literati nevertheless shared command of the painter's chief tool: the brush. Literati came to idealize the model of the scholar who so embodied the evolved patterns of civilization that his character could be viewed and appreciated through the dynamics of his brushwork. They saw themselves overcoming any lack of technical expertise with the far more substantial values of cultural and ethical virtue, expressed kinetically and aesthetically.

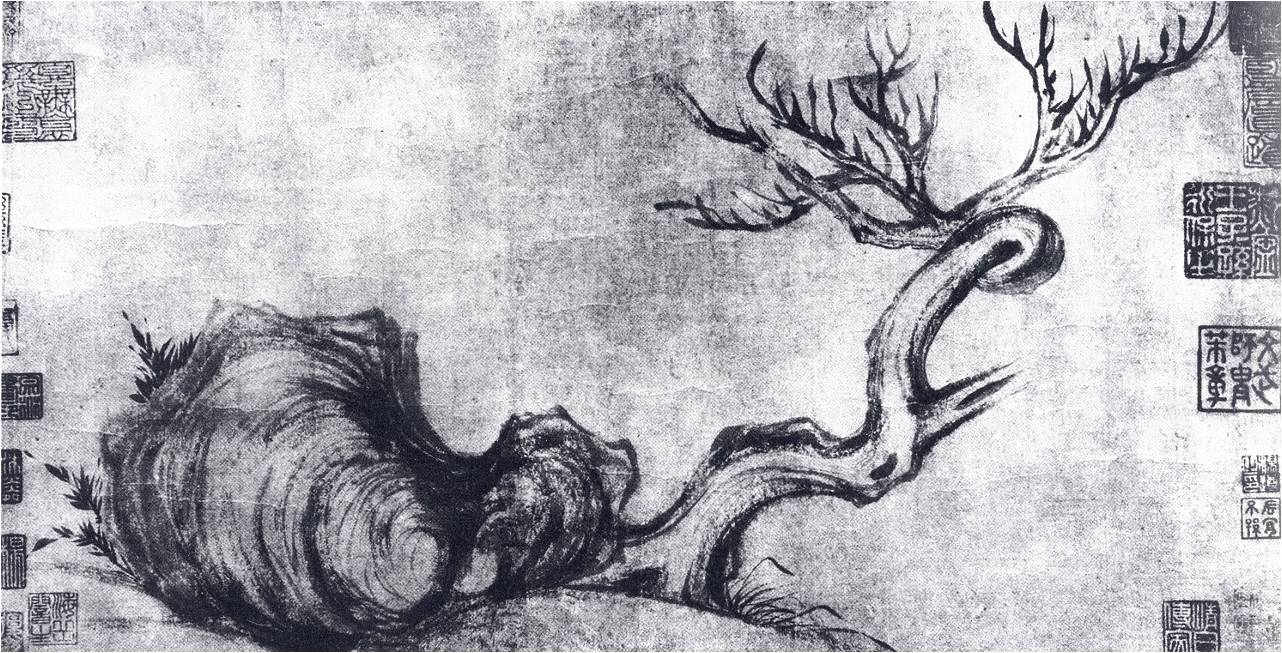

One of the first to set a new standard of artistic excellence - in stark contrast to the intricate delicacy of monumental academic art - was Su Shi (also known as Su Dongpo, 1037-1101), a brilliant poet, fine calligrapher, and virtuoso scholar-official. Su Shi's "Ancient Tree with Rock," below, highlights the calligraphic elements of the brush strokes by simplifying the form (not even bothering to complete features of the tree). Su Shi's painting resonates with simplified paintings associated with Song era Zen (Chan) Buddhism (discussed on page 8, below), and prefigures the rich tradition of literati painting that, as we will see, reached its first full flowering during the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368).