| General East Asia survey course materials - R. Eno |

The Samurai-Merchant Divide in Late

Tokugawa, and Tokugawa Popular Art

The Tokugawa economy

During the earliest years of the Tokugawa period (1600-1868), the shogun's

government ordered Japan "closed" to contacts with outside

countries. This policy was initially intended to stabilize internal social

and political life, avoiding the chance for any possible competitor of the shōgun's

power to mobilize resources and samurai in quest of external conquest and

revival of warrior activity. It was also part of a very broad attack on

other potential threats to shogunal supremacy, which notably included a

nationwide persecution of foreign missionaries and Christian converts that

virtually wiped Christianity out in Japan for centuries -- until this time,

Christianity had been a vital growing force in Japanese society, having been

introduced as early as the 1540's, the time of the initial arrivals of Western

traders in Japan.

While Japan's closing was not truly complete -- minimal trade

with Dutch, Chinese, and Korean representatives at the port of Nagasaki

continued to be permitted -- it had a powerful impact on the Japanese

economy. While it is possible, looking back, to wonder whether Japan's

economy would not have grown more quickly if the nation had been open to trade,

in Japan's case, there were powerful economic forces in operation domestically,

and sealing off the state seems to have acted as a spur for internal

development.

Traditionally, wealth had been conceived in terms of land and

its produce, and d

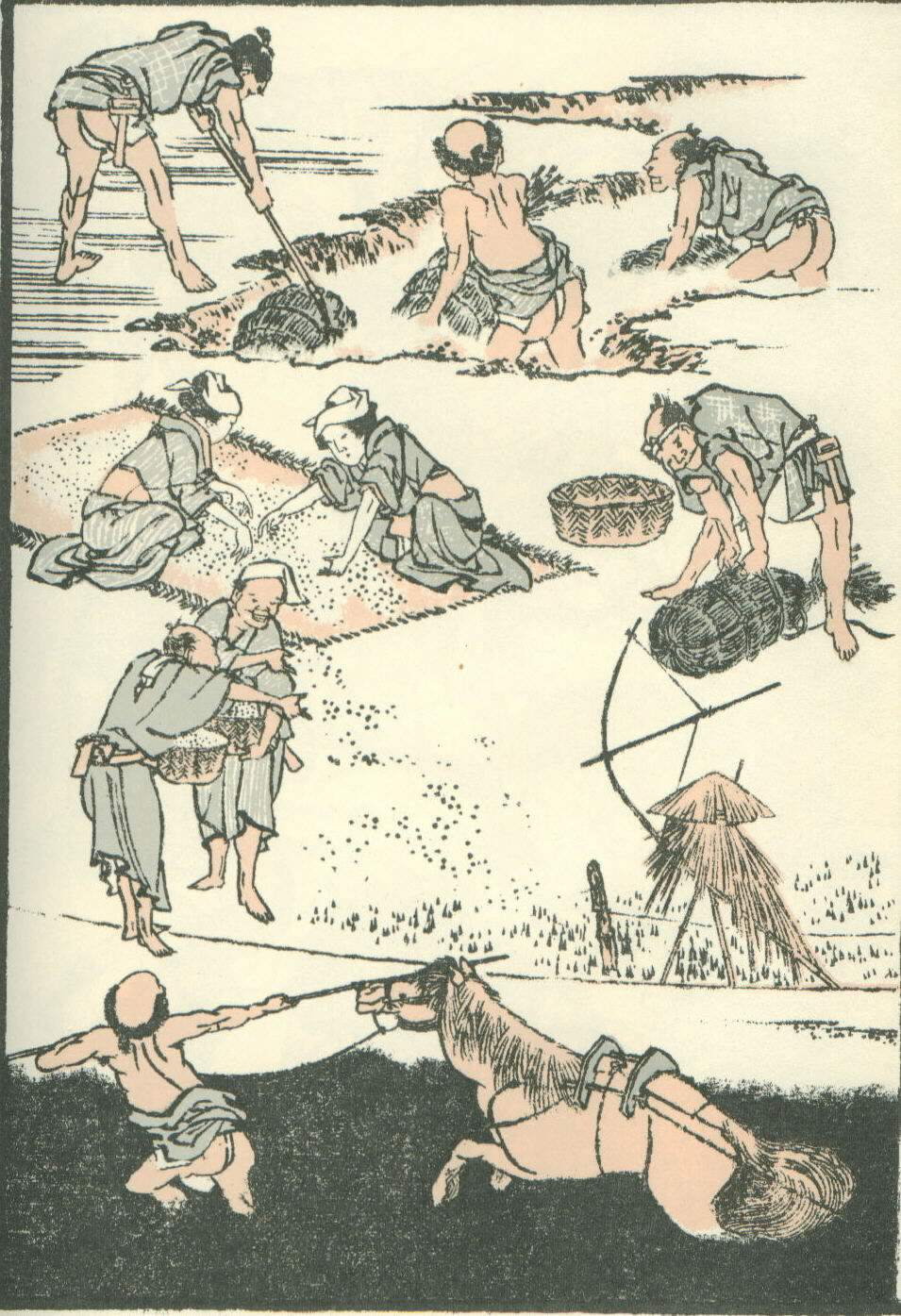

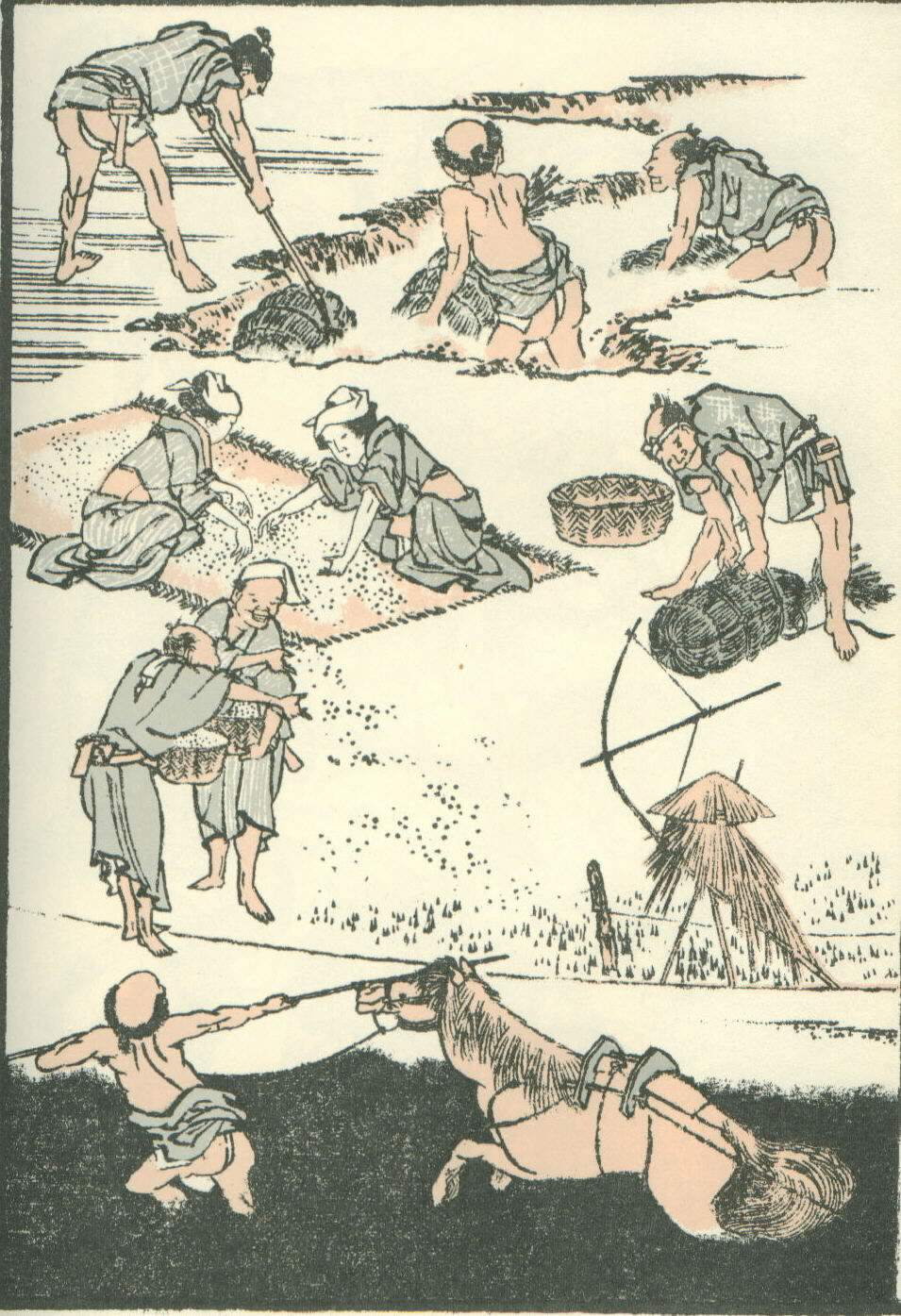

Traditionally, wealth had been conceived in terms of land and

its produce, and d uring the Tokugawa, this continued to be the case. Taxes

were principally charged on land holdings, and officially distributed wealth --

in particular, the fixed stipends on which the samurai class lived -- were

calculated and delivered in terms of measures of rice, the staple crop of

Japan. (A sketch page of rice-growing activities by the great woodblock

artist Hokusai appears at left, and a rare photo of a Tokugawa era farmer at

right.) Commerce was taxed

very lightly. Structurally, this placed the commercial sector in an

unplanned advantageous position, as compared with peasant and samurai classes.

uring the Tokugawa, this continued to be the case. Taxes

were principally charged on land holdings, and officially distributed wealth --

in particular, the fixed stipends on which the samurai class lived -- were

calculated and delivered in terms of measures of rice, the staple crop of

Japan. (A sketch page of rice-growing activities by the great woodblock

artist Hokusai appears at left, and a rare photo of a Tokugawa era farmer at

right.) Commerce was taxed

very lightly. Structurally, this placed the commercial sector in an

unplanned advantageous position, as compared with peasant and samurai classes.

The political structure of Tokugawa society also favored the

development of trade in two key respects. First, the shogunate had ordered

that the daimyō, located throughout the country on their large landed

estates, or han, organize their samurai governance along Confucian lines,

like the shogun's government in the eastern city of Edo (Tokyo).

This requirement for centralized governance for each local domain led to

the growth of urban nodes throughout Japan -- a great spur for commerce, and the

concentration of wealth in a manner that leads to trade in luxury goods.

Even more important was the shogunal requirement that daimyo

from all regions of Japan travel each year to Edo and maintain a residence

there, where they would reside for half of each year -- their close family

remaining there as "hostages" to loyal daimyo behavior during

the other portion of the year.

The procession each year of the wealthiest

and most prestigious members of society and their extensive retinues to and from

the capital was an enormous income generator for merchants -- and a great drain

on the resources of the daimyō. It also led to the development of a

vast network of high quality roads, which spurred the development of

inter-regional trade. (Part of a scroll depicting a daimyō's

procession to the capital is pictured at right.)

The procession each year of the wealthiest

and most prestigious members of society and their extensive retinues to and from

the capital was an enormous income generator for merchants -- and a great drain

on the resources of the daimyō. It also led to the development of a

vast network of high quality roads, which spurred the development of

inter-regional trade. (Part of a scroll depicting a daimyō's

procession to the capital is pictured at right.)

The han which had the greatest land and population

resources, and which developed the greatest urban node as the base of its

governance activity, was the shogun's own territory -- vast stretches of

land reaching from Edo in the east to Kyoto -- the former capital of Heian -- in

the central region of the main island of Honshu. Consequently, the capital

city of Japan, Edo, began to grow during the Tokugawa into the great city that

has become Tokyo today. By the 18th century, Edo was one of, or perhaps

the largest city in the world, with a population approaching a million

people. To sustain this growth, the government sponsored policies that

would enlarge production and trade in non-agricultural sectors. Merchants

were encouraged to develop large businesses, and the government reversed earlier

policies restricting trade associations; consequently, large groups of merchants

-- or more properly, merchant families -- promoted their businesses through a

mixture of competitive and cooperative behavior that proved very beneficial to

large-scale growth, a pattern that continued into and through the 20th century.

Impact on the samurai

Commercial growth and the beginnings of industrial

development and urban concentration of production led to inflationary prices

throughout most of the Tokugawa era. This had a severe impact on the

samurai living distant from Edo, serving their daimyō lords on their han.

The samurai were allocated fixed stipends according to a system developed at the

start of the Tokugawa era, and the daimyō were largely dependent on

agriculture for income -- land taxes being the primary source of government

wealth. Food prices could not rise at the rates of other goods because the

demand for food was spread among all members of society, rich and poor, and

overly high prices could quickly cut demand. This limited daimyō income.

On the other hand, the daimyō could not afford to allow themselves to

slip into poverty -- on the contrary, as power holders over their samurai and

the common people, it was essential that they maintain a lifestyle commensurate

with their prestige, both on their han and in their required trips to

Edo. This led the daimyō to borrow funds to sustain their social

and material needs as cash ran low; the increasingly rich merchant class thus

became moneylenders to the daimyō, ensuring a further transfer of wealth

from the samurai class to the merchant class. Other samurai, whose fixed

stipends were losing value over the generations, began actively to farm in order

to generate additional income. But with food prices rising more slowly

than other prices, this was only a half-measure. Ultimately, many samurai

voluntarily discarded the privileged class status they enjoyed, and left the

service of their daimyō lords and re-registered as common people, in

order to be able to engage in small business or the production of cottage goods,

like sandals and baskets, types of commercial activities that were prohibited to

samurai because they were beneath the dignity of the class.

All of this generated bitter resentment. The samurai,

seeing their class -- the elite of society -- fall into poverty while the

merchants -- officially social scum -- rising rapidly in wealth, became bitter

enemies of the merchants, and of merchant values and culture.

Merchant culture

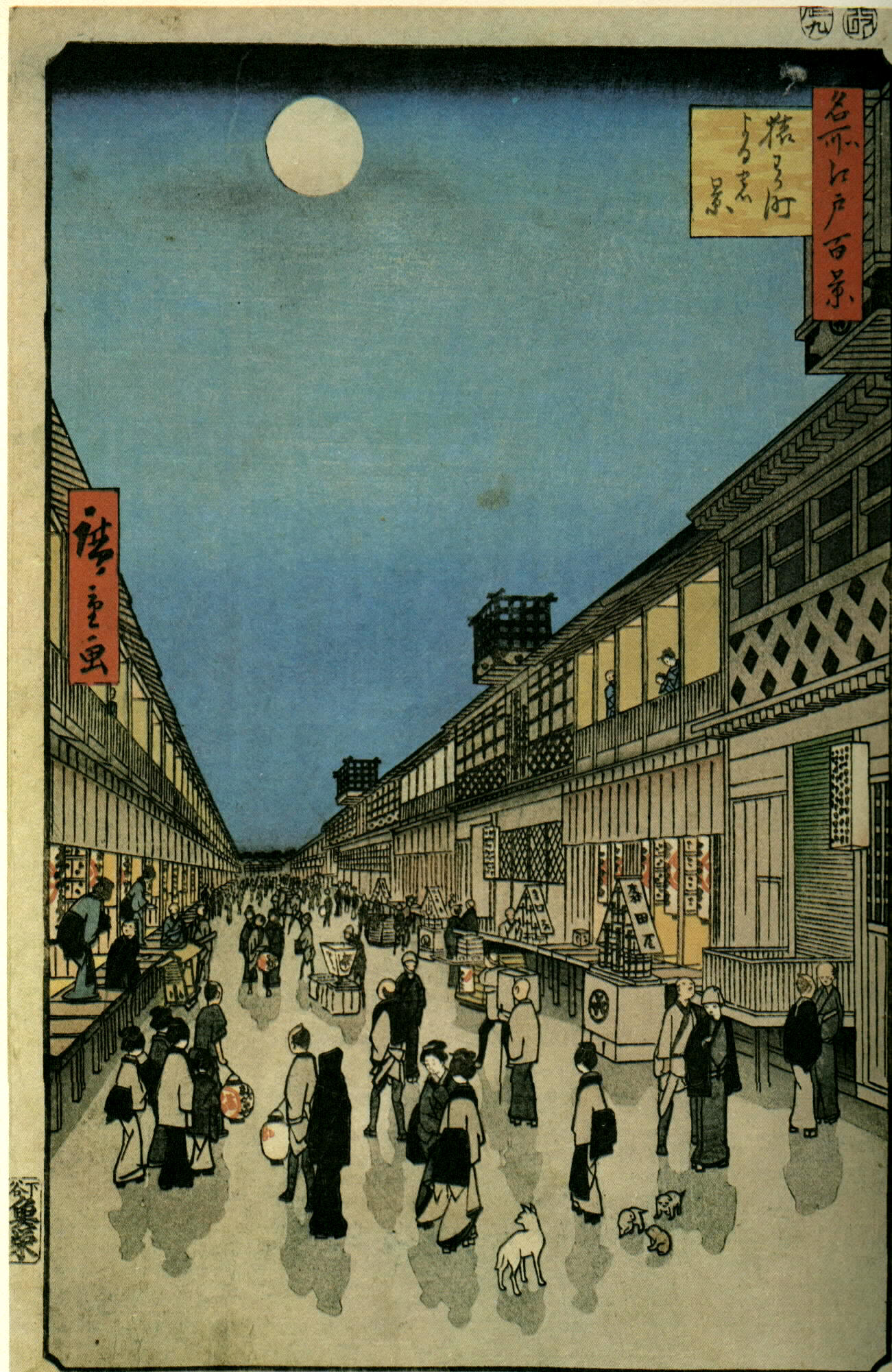

The urbanization of Tokugawa Japan and the rising wealth of

those immersed in commerce led to the growth of a new type of urban

culture,  placing great value on sensual luxury, entertainment, and leisure arts. It

was these features of culture which the samurai, steeped in the austerity of the

bushido warrior codes and Zen Buddhism deplored. Urban centers of

conspicuous consumption, such as the "pleasure quarters" of shops, theaters, and

brothels, began to appear in all major cities -- most notably

Edo (the entrance to Edo's famous Yoshiwara pleasure district is pictured at

left). A literature focused on romance began to spread (the merchant class

at all levels was remarkably literate in Tokugawa Japan), styles in clothes

became increasingly lavish, and a cult of sexual indulgence grew in importance

(Japan had never been as prudish or moralistic as most cultures, something

expressed in the relaxed non-moralistic character of the native religion of

Shinto). The role played by "courtesans" (young women, often highly

trained in polite arts, who granted favors of companionship and sex for

money; pictured below) became a highly visible feature

of the urban culture of the merchant class.

placing great value on sensual luxury, entertainment, and leisure arts. It

was these features of culture which the samurai, steeped in the austerity of the

bushido warrior codes and Zen Buddhism deplored. Urban centers of

conspicuous consumption, such as the "pleasure quarters" of shops, theaters, and

brothels, began to appear in all major cities -- most notably

Edo (the entrance to Edo's famous Yoshiwara pleasure district is pictured at

left). A literature focused on romance began to spread (the merchant class

at all levels was remarkably literate in Tokugawa Japan), styles in clothes

became increasingly lavish, and a cult of sexual indulgence grew in importance

(Japan had never been as prudish or moralistic as most cultures, something

expressed in the relaxed non-moralistic character of the native religion of

Shinto). The role played by "courtesans" (young women, often highly

trained in polite arts, who granted favors of companionship and sex for

money; pictured below) became a highly visible feature

of the urban culture of the merchant class.

The

life of the urban pleasure quarters became known as ukiyo, the

"floating life," and themes of this new culture became an emblematic

focus of Tokugawa art and literature. Among the most famous features of

this merchant culture was the innovation of a new form of art -- the woodblock

print -- and many brilliant artists of the era captured the spirit of the new

merchant culture -- as well as the spirit of many traditional Japanese values,

in the brilliant prints of the era, such as those which appear on this page.

The

life of the urban pleasure quarters became known as ukiyo, the

"floating life," and themes of this new culture became an emblematic

focus of Tokugawa art and literature. Among the most famous features of

this merchant culture was the innovation of a new form of art -- the woodblock

print -- and many brilliant artists of the era captured the spirit of the new

merchant culture -- as well as the spirit of many traditional Japanese values,

in the brilliant prints of the era, such as those which appear on this page.

Kabuki

One of the most prominent influences on merchant culture

during the Tokugawa was the rise of a form of theatrical staging known as Kabuki

-- a type of operatic popular theater that feature lively action, sensational

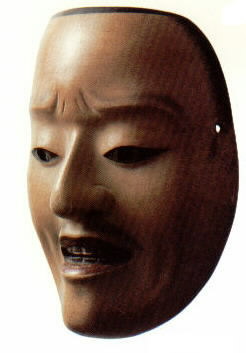

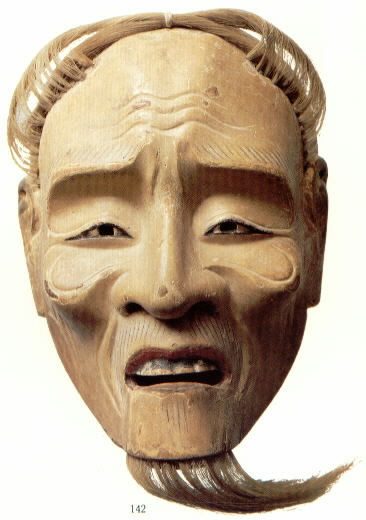

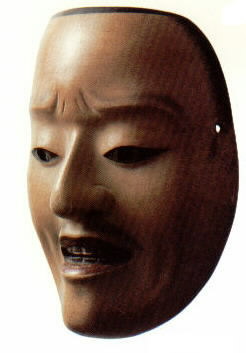

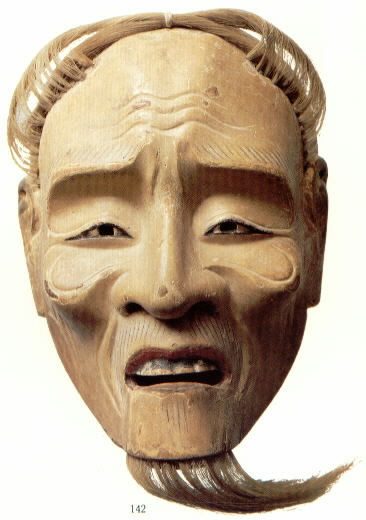

plots, and colorful costume and stage make-up. Prior to Kabuki, the most

important form of staged theatrical in Japan was the austere spectacle of Noh

(or Nō) drama. Initially inspired by

Shinto religious pageantry,

Noh was (and is) a

stripped-down form of stage play, characterized by simple and serious plots,

intense symbolism, and focused interaction between a small number of actors,

often only two or three, wearing simple but striking masks (such as the two at

left). Noh drama was

somber and spare, and appealed to the aesthetic of the samurai class,

resonating as it did with the values of Zen Buddhism. During the Tokugawa

era, Noh was regarded as a classical form of theater. It had originated as

early as the thirteenth century and been patronized by shoguns and daimyos for

many centuries. Interest in Noh was regarded as a sign of superior taste

(and it remains so today).

Noh was (and is) a

stripped-down form of stage play, characterized by simple and serious plots,

intense symbolism, and focused interaction between a small number of actors,

often only two or three, wearing simple but striking masks (such as the two at

left). Noh drama was

somber and spare, and appealed to the aesthetic of the samurai class,

resonating as it did with the values of Zen Buddhism. During the Tokugawa

era, Noh was regarded as a classical form of theater. It had originated as

early as the thirteenth century and been patronized by shoguns and daimyos for

many centuries. Interest in Noh was regarded as a sign of superior taste

(and it remains so today).

Kabuki theater was far more raucous, musical, and fun. Kabuki

originated just at the start of the Tokugawa era as a song-and-dance act,

performed by female dance troupes. Daring and lewd, the shogunate viewed

these early stagings as a threat to public order and banned female dancers from

performing them. Young boys were then recruited to the fledgling Kabuki

troupes, but they were seen as equally erotic and dangerous, and it was only

when adult male actors alone were permitted to perform -- all female roles being

taken by males in drag costume -- that the legal status of Kabuki was

established (though periodic crackdowns on its excesses occurred). In the capital

city of Edo, Kabuki became a dominant cultural form (much like opera in Italian

cities like Naples), of interest to people of all classes, but particularly the

merchant class. Kabuki plays ranged from re-creations of great tales of the

high tide of samurai militarism to relatively realistic romances of more

"modern" life. Great Kabuki actors were a social

sensation, much like movie stars today, and images of them performing great

roles (particularly as samurai or impersonating female characters) were

everywhere, like modern movie posters.

The woodblock image of an Edo Kabuki theater below

conveys the sense of stage flamboyance and audience bustle that made Kabuki an

urban sensation -- note the runways that extend through the audience, bringing

audience and actors close together.

Ukiyo-e Art

No facet of Tokugawa art better reflects the popular culture

of the era than the woodblock images of Edo culture,

known as ukiyo-e: "sketches of the floating world." A major force in world visual art, the themes of

the Tokugawa ukiyo-e artists express a vast range of cultural features

exciting to the observer -- and often infuriating to the samurai of the times.

Ukiyo-e art, cheap, available, ubiquitous in the urban centers where the

wealthy and despised merchant families lived, was licentious and lewd,

outrageous in its depictions of samurai through Kabuki stage caricature, and

equally appreciative of the aesthetics of nature and society, with none of the

sense of disciplined taste that characterized the art most valued by the samurai

elite.

Ukiyo-e is central to our vision of the Tokugawa era,

and we will explore it further in today's web reading (most of the images on

this page are examples of woodblock art).

NOTE: Please note that on the pages that follow, there are names and dates for a variety of ukiyo-e

artists -- these will not be items for testing; they are they to provide

information and a fuller sense of historical context as you read these pages.

Hiroshige: Edo at night

Traditionally, wealth had been conceived in terms of land and

its produce, and d

Traditionally, wealth had been conceived in terms of land and

its produce, and d uring the Tokugawa, this continued to be the case. Taxes

were principally charged on land holdings, and officially distributed wealth --

in particular, the fixed stipends on which the samurai class lived -- were

calculated and delivered in terms of measures of rice, the staple crop of

Japan. (A sketch page of rice-growing activities by the great woodblock

artist Hokusai appears at left, and a rare photo of a Tokugawa era farmer at

right.) Commerce was taxed

very lightly. Structurally, this placed the commercial sector in an

unplanned advantageous position, as compared with peasant and samurai classes.

uring the Tokugawa, this continued to be the case. Taxes

were principally charged on land holdings, and officially distributed wealth --

in particular, the fixed stipends on which the samurai class lived -- were

calculated and delivered in terms of measures of rice, the staple crop of

Japan. (A sketch page of rice-growing activities by the great woodblock

artist Hokusai appears at left, and a rare photo of a Tokugawa era farmer at

right.) Commerce was taxed

very lightly. Structurally, this placed the commercial sector in an

unplanned advantageous position, as compared with peasant and samurai classes. The procession each year of the wealthiest

and most prestigious members of society and their extensive retinues to and from

the capital was an enormous income generator for merchants -- and a great drain

on the resources of the daimyō. It also led to the development of a

vast network of high quality roads, which spurred the development of

inter-regional trade. (Part of a scroll depicting a daimyō's

procession to the capital is pictured at right.)

The procession each year of the wealthiest

and most prestigious members of society and their extensive retinues to and from

the capital was an enormous income generator for merchants -- and a great drain

on the resources of the daimyō. It also led to the development of a

vast network of high quality roads, which spurred the development of

inter-regional trade. (Part of a scroll depicting a daimyō's

procession to the capital is pictured at right.) placing great value on sensual luxury, entertainment, and leisure arts. It

was these features of culture which the samurai, steeped in the austerity of the

bushido warrior codes and Zen Buddhism deplored. Urban centers of

conspicuous consumption, such as the "pleasure quarters" of shops, theaters, and

brothels, began to appear in all major cities -- most notably

Edo (the entrance to Edo's famous Yoshiwara pleasure district is pictured at

left). A literature focused on romance began to spread (the merchant class

at all levels was remarkably literate in Tokugawa Japan), styles in clothes

became increasingly lavish, and a cult of sexual indulgence grew in importance

(Japan had never been as prudish or moralistic as most cultures, something

expressed in the relaxed non-moralistic character of the native religion of

Shinto). The role played by "courtesans" (young women, often highly

trained in polite arts, who granted favors of companionship and sex for

money; pictured below) became a highly visible feature

of the urban culture of the merchant class.

placing great value on sensual luxury, entertainment, and leisure arts. It

was these features of culture which the samurai, steeped in the austerity of the

bushido warrior codes and Zen Buddhism deplored. Urban centers of

conspicuous consumption, such as the "pleasure quarters" of shops, theaters, and

brothels, began to appear in all major cities -- most notably

Edo (the entrance to Edo's famous Yoshiwara pleasure district is pictured at

left). A literature focused on romance began to spread (the merchant class

at all levels was remarkably literate in Tokugawa Japan), styles in clothes

became increasingly lavish, and a cult of sexual indulgence grew in importance

(Japan had never been as prudish or moralistic as most cultures, something

expressed in the relaxed non-moralistic character of the native religion of

Shinto). The role played by "courtesans" (young women, often highly

trained in polite arts, who granted favors of companionship and sex for

money; pictured below) became a highly visible feature

of the urban culture of the merchant class. The

life of the urban pleasure quarters became known as ukiyo, the

"floating life," and themes of this new culture became an emblematic

focus of Tokugawa art and literature. Among the most famous features of

this merchant culture was the innovation of a new form of art -- the woodblock

print -- and many brilliant artists of the era captured the spirit of the new

merchant culture -- as well as the spirit of many traditional Japanese values,

in the brilliant prints of the era, such as those which appear on this page.

The

life of the urban pleasure quarters became known as ukiyo, the

"floating life," and themes of this new culture became an emblematic

focus of Tokugawa art and literature. Among the most famous features of

this merchant culture was the innovation of a new form of art -- the woodblock

print -- and many brilliant artists of the era captured the spirit of the new

merchant culture -- as well as the spirit of many traditional Japanese values,

in the brilliant prints of the era, such as those which appear on this page.

Noh was (and is) a

stripped-down form of stage play, characterized by simple and serious plots,

intense symbolism, and focused interaction between a small number of actors,

often only two or three, wearing simple but striking masks (such as the two at

left). Noh drama was

somber and spare, and appealed to the aesthetic of the samurai class,

resonating as it did with the values of Zen Buddhism. During the Tokugawa

era, Noh was regarded as a classical form of theater. It had originated as

early as the thirteenth century and been patronized by shoguns and daimyos for

many centuries. Interest in Noh was regarded as a sign of superior taste

(and it remains so today).

Noh was (and is) a

stripped-down form of stage play, characterized by simple and serious plots,

intense symbolism, and focused interaction between a small number of actors,

often only two or three, wearing simple but striking masks (such as the two at

left). Noh drama was

somber and spare, and appealed to the aesthetic of the samurai class,

resonating as it did with the values of Zen Buddhism. During the Tokugawa

era, Noh was regarded as a classical form of theater. It had originated as

early as the thirteenth century and been patronized by shoguns and daimyos for

many centuries. Interest in Noh was regarded as a sign of superior taste

(and it remains so today).