Ukiyo-e Themes and Tokugawa Culture, 2: Popular Entertainment

One of the most notable features of Tokugawa urban culture was the popularity of spectacles -- in particular of Kabuki plays and of the boisterous competitions of huge sumo wrestlers, whose matches were, perhaps, enactments of the popular notions of warrior battles that belonged to the samurai past (though certainly caricatured by the grossly overfed forms of the sumo contestants).

In this regard, ukiyo-e became something like poster art -- the woodblock images were not only sold, they were posted on pillars and other places to enhance public awareness of Kabuki theaters and sumo matches. The greatest actors and wrestlers enjoyed a centrality to popular culture much like today's movie stars (sumo wrestlers still retain some of this mystique in Japan today).

In the woodblock prints of Tokugawa Japan, we also begin to see features of fantastic drawing styles that evolved into manga forms -- manga denoting free-form sketching and also serving as the name given to "comic books" in Japan today. The movement in this direction can be seen in the images here. The image at left is by Kiyonobu (1664-1729), who was one of the early popularizers of Kabuki actors in ukiyo-e. The image is not of a young samurai, as it might appear, but of a popular actor of the time appearing onstage in the garb of a samurai. The graceful line and brocaded design capture the stage reality of the samurai, presented for the viewing pleasure of a population of urban merchants and artisans, rather than the image the samurai class presented itself. (By the way, the swastika on the actor's robe is associated with Buddhism, where it denotes good fortune and carries the meaning of ten thousand, as in a life of ten thousand years.) The image at right, by a follower of Kiyonobu's, known as Kiyomasu (1694-1716), illustrates the comic-book like quality that ukiyo-e artists introduced to convey the dynamism of dramatic action onstage, particularly in portraits of warriors in action.

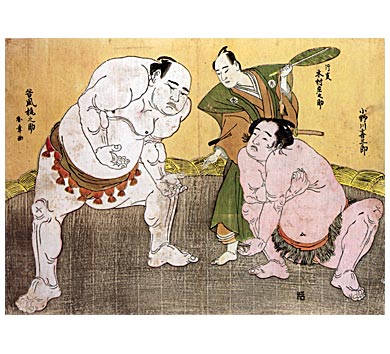

The ukiyo-e artist Shunsho (1726-1792) applied other styles to actor portraits, and also pioneered the celebration of sumo wrestlers. The dramatic actor print at left below conveys through dramatic composition the impact of the stage samurai lord (complete with patterned face make-up. The central print shows sumo wrestlers preparing to do battle, a referee overseeing the match. At right is one of a series that Shunsho created to celebrate the exciting development of a great sumo prodigy -- a child whose enormous height and weight at a very young age promised to make him the greatest wrestler of all time. Edo society was thrilled with the prospect of watching the boy grow into a behemoth of the wrestling ring and Shunsho's prints served to help promote his career (which, in the end, turned out to be a disappointment).

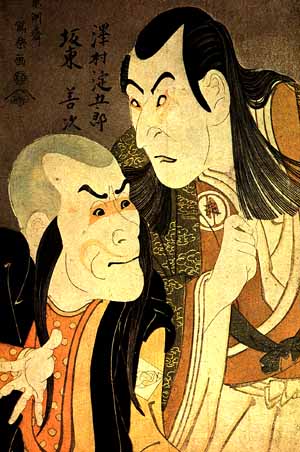

In 1794, the greatest of all Kabuki portraitists appeared suddenly. His name was Sharaku and for ten months in 1794-95 he produced actor prints of astonishing immediacy and daring design. The he disappeared as suddenly as he had arrived -- to this day, no one is certain who Sharaku actually was. Among the three images below, all portraying Kabuki actors in character, the one at right is particularly worth noting, as it reflects the popular interest in onnagata -- Kabuki female impersonators. Certain Kabuki actors devoted their careers to portrayal of female characters on stage, and their transvestite personas were among the most celebrated in Tokugawa urban society. This is yet another feature of the sexual daring of popular culture during the Tokugawa era. Throughout the period, theater, printmaking, fiction, and other art forms were closely regulated by the shogun's government, in an attempt to assert samurai control over a culture that was building a life of its own.

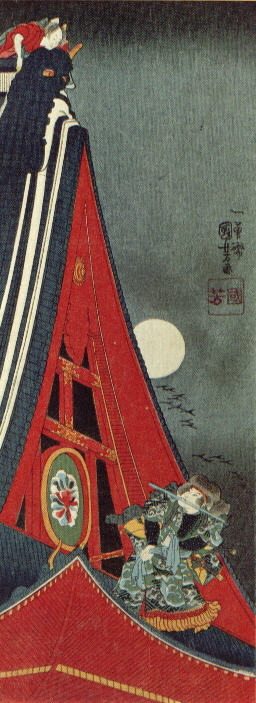

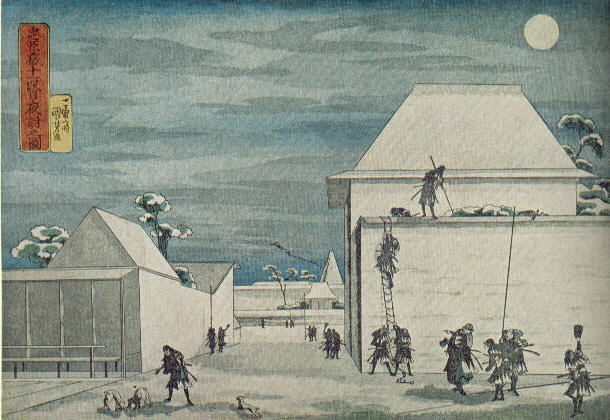

The final artist represented on this page, Kuniyoshi

(1798-1861), moved ukiyo-e depictions of drama

into a new area by conceiving Kabuki

plots

and the tales of a growing body of popular fiction in real space, rather than in

stage space. Using techniques of perspective and composition clearly

influenced by Western art (which was known to some degree in Japan because of

the tightly controlled trade in cultural objects that continued throughout the

Tokugawa era between Dutch traders and Japanese at the port of Nagasaki -- the

sole authorized point of contact between Japan and the outside world). In

the three images here, we see Kuniyoshi illustrating, in the image at left and

the one below scenes,

events from traditional tales dramatized in Kabuki theater, but freed from the

confines of the stage, allowing dramatically imaginative compositional elements.

The large image at the bottom of this page, composed of three separate prints that were issued as a "triptych,"

or tri-part image, illustrates with great innovation a grotesque scene from a

popular novel of the mid-nineteenth century, towards the close of the Tokugawa.

The final artist represented on this page, Kuniyoshi

(1798-1861), moved ukiyo-e depictions of drama

into a new area by conceiving Kabuki

plots

and the tales of a growing body of popular fiction in real space, rather than in

stage space. Using techniques of perspective and composition clearly

influenced by Western art (which was known to some degree in Japan because of

the tightly controlled trade in cultural objects that continued throughout the

Tokugawa era between Dutch traders and Japanese at the port of Nagasaki -- the

sole authorized point of contact between Japan and the outside world). In

the three images here, we see Kuniyoshi illustrating, in the image at left and

the one below scenes,

events from traditional tales dramatized in Kabuki theater, but freed from the

confines of the stage, allowing dramatically imaginative compositional elements.

The large image at the bottom of this page, composed of three separate prints that were issued as a "triptych,"

or tri-part image, illustrates with great innovation a grotesque scene from a

popular novel of the mid-nineteenth century, towards the close of the Tokugawa.

|

|