Western Zhou Inscription Project

Note for online readers. In G380, the principal way the Western Zhou as studied was through the primary texts of contemporary bronze inscriptions. The "Inscriptional Records" reading consisted of translations of over 130 inscriptions. Students worked in groups of five, each group assigned a specific topic range to explore. The groups met to discuss their plans for a coherent presentation on the day following Class #26, and then an entire week was devoted to group presentations and class questions about and discussion of group findings. Those four classes are basically "missing" from this archived course site (there were no preparation pages or PowerPoints), but students generally welcomed the project -- it meant that for over a week, I said virtually nothing! |

Reading: History of the Western Zhou, Inscriptional Records of the Western Zhou, pp. 1-4 + your assigned inscriptions

At our next meeting, I'll briefly survey the history of the Western Zhou, as it's recorded in the Shiji -- this record constitutes your reading for Thursday, but you may skim this reading at this point -- during the group project work we'll be doing, you'll be referring to it, and can absorb it further as you do that work.

After the survey, we'll start to look closely at the inscriptions. For this, you should read closely p. 1 of the inscriptional reading plus the page you're reading now. On this page, I'll give an example of how an inscription is read. Read closely, and we'll discuss further in class how information can be extracted from these texts.

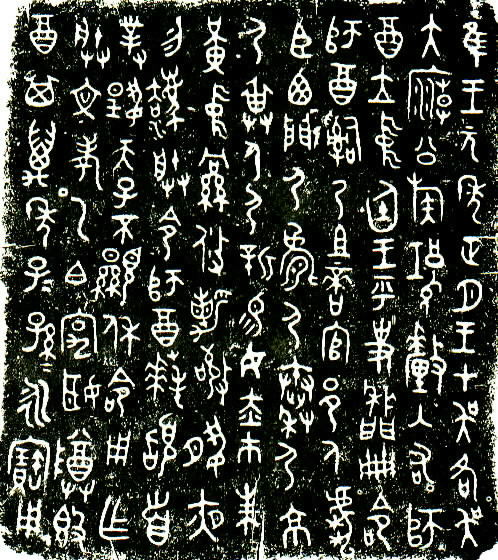

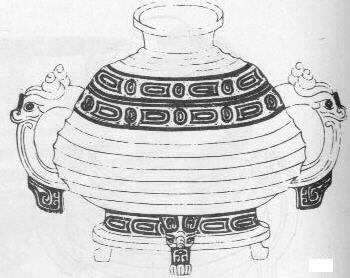

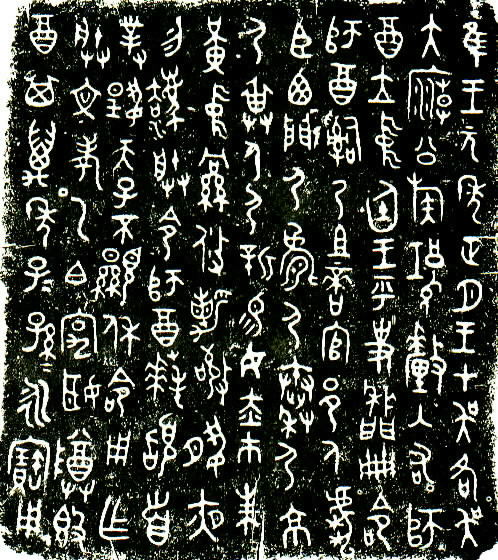

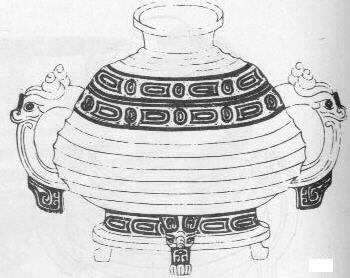

Below is a copy of an inscription found in your collection of translations, the Shi You gui (or "Commander You's tureen," #61), alongside a sketch of the vessel itself (now lost). Continue down below these images to see how the inscription is read - I've broken the text into 12 sections.

The inscription, like all bronze inscriptions, is read from the upper right hand corner down, row by row. Starting from the top right, then, the first "sentence" is the date/time formula. If you read the discussion of the inscription below, you'll see how most of the features of a "typical" inscription, as described in the reading on Western Zhou bronze inscriptions, page 1, appear in the text of Commander You's tureen.

[Note: Formatting this page was a bit difficult, and different browsers will present it differently; the intent is that all the inscription text runs down the left side of the page without overlap.]

Section 1

![]()

Literally [these literal readings will give one English word per Chinese character]: "Well, King initial year beginning month, King at Wu."

Translation: "It was in the King's first year, in the first month, when the King was at Wu."

Comment: This conforms with the standard dating style described on p. 1 of the inscription reading, in paragraph 1.

. . . continuing on . . .

Section 2

Literally: "Descended Wu great temple."

Translation:

"The King descended to the Great Temple of Wu."

Translation:

"The King descended to the Great Temple of Wu."

Comment: I'm unsure where this would be.

Section 3

![]()

Literally: "Gong [elder, or duke] clan X Li enter assist Commander You,"

Translation: "Li, the Gong of the lineage X, entered accompanying Commander You,"

Comment: The term gong can denote a

"feudal" rank, or simply be used as a term of respect for a senior

member of a clan lineage. As the reading explains on p. 1, wherever

the letter X appears alone, it signifies a Chinese character I can't decipher

(or, more accurately, which I've found no commentary scholarship

deciphering). In this case, the character is ![]() .

.

(This is You's name; it's linked to the text above.)

Section 4

![]()

Literally: "Stand center courtyard."

Translation: "[Shi You] took his place at the center of the court."

Comment: The "accompanying" of a patrician to the center of court by another, prior to an address by the King, is a commonly seen verbal formula in the bronzes, and is of interest in describing Western Zhou li.

Section 5

![]()

Literally: "King calls recorder Qiang bamboo-strip-cluster order Commander You,"

Translation: "The King called out to Recorder Qiang to recite the written order to Commander You,"

Comment: This is a commonly seen verbal formula in the context of a court ritual charging a patrician with rank or office. Bamboo strips were the medium used for writing -- the "paper" of the time. here Recorder Qiang seems to have already prepared a written order from the King to Commander You, and at the King's command, he reads it out aloud in court. This common formula gives us insight into court ritual, conventions of writing, and the way in which hierarchy in government rank was articulated.

![]()

Section 6

![]()

Literally: "Oversee your ancestor hereditarily officiate town people, tiger minister Xi-men ( = 'Westgate') Yi-people (non-Chinese peoples of the East), Quan Yi-people, Qin Yi-people, Jing Yi-people, X-shen Yi-people."

Translation: "Assume your ancestors’ hereditary office over the townsmen and over the tiger braves from the Yi people of Xi-men, the Yi of Quan, the Yi of Qin, the Yi of Jing, and the Yi of X-shen."

Comment: "Tiger braves" denotes

elite warriors. Here we see that Commander You is, in this court ceremony,

succeeding to a role that his father and grandfather had played before

him. He must be the eldest son of his clan branch, and the clan must have

a longstanding military role in controlling non-Chinese peoples in the eastern

regions of the Zhou polity. This section gives us information about the

relationship between Chinese and non-Chinese peoples at the beginning of King

Gong's reign.

![]()

![]()

Section 7

![]()

The first three characters read, literally, "New give you," which seems to mean that the King is presenting Commander You with certain objects that signify his office, objects which his father had previously owned (Commander You may have brought these to court himself, bearing his late father's insignia so that the King could bestow them upon him, or perhaps these are indeed newly made objects).

Literally: "New give you red apron, vermillion sash yellow interior, bronze-adorned bridle"

Translation: "I newly present you with a red apron and vermillion sash with buff- colored belt, and a bronze adorned bridle."

Section 8

Literally: "Alert day night, don't discard My command."

Translation: "Be assiduous day and night, never disobeying my orders."

Comment: The word for "my" (which appears as the next to last character in this section) is a pronoun that all ancient commentary texts agree was reserved solely for the King's use. However, we'll see the pronoun used by Commander You below -- I have no explanation, except that the commentators were clearly misinformed! [Obviously, this is a point that you would not get from the translations alone.]

Section 9

![]()

Literally: "Commander You hands-to-forehead-bow floor-knock head."

Translation: "Commander You bowed prostrate."

Comment: This is standard wording to describe the act later called the kow-tow, which involved, here, kneeling with the hands at the forehead, and lowering one's head to the floor.

Section 10

![]()

Literally: "Facing raise Heaven's son's shining brilliant gift."

Translation: "[Commander You] raised in thanks the brilliant grace of the Son of Heaven."

Comment: It is unclear whether the grantee of gifts such as the ones Commander You received actually held the gifts in hand as this action was taken, or whether he simply uttered some words of thanks and praise, but the formula is very common in the inscriptions.

![]()

Section 11

21![]()

Literally: "Order use [to] make My patterned (wen) late-father Bo-Elder-Yi [and] Qiu Ji-clan-woman exalted tureen."

Translation: "[Commander You] ordered to be cast this tureen for my patterned father Yi Bo and [mother] Qiu Ji."

![]()

Comment: The formula suggests that the gifts were "used" to make the vessel in which this inscription appears. In some inscriptions, we see patricians actually receiving "metals," and in those cases, it may be that the formula literally signifies this idea. Here, it seems just to mean that the vessel was cast on the occasion of this ceremony. "Bo" is a term that means "elder," but it can also signify a "feudal" rank, "earl." We can't know which is correct. We learn here that Commander You's mother was a member of the Zhou royal Ji clan (his father, then, was not), which gives us a good picture of his relationship to the King

![]()

Section 12

Literally: "[Commander] You may 10,000 years sons sons grandsons grandsons, forever treasure use."

Translation: "May You’s descendants treasure it forever."

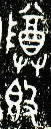

Comment: This is a very common

formula. Note that the reduplicated "sons" and

"grandsons" appear on the inscription in the form of short doubled

lines on the right side of the characters, as in ![]() ;

this is an early type of ditto mark. In understanding the motive behind

the casting of these inscriptions, it's important to pay attention to these

closing phrases -- although we tend to overlook them because they are so routine

and formulaic.

;

this is an early type of ditto mark. In understanding the motive behind

the casting of these inscriptions, it's important to pay attention to these

closing phrases -- although we tend to overlook them because they are so routine

and formulaic.